March 1, 2021

2021 Northeast Fisheries Outlook

Contents

Volume 15, Issue 3

March 2021

Click here for a PDF version of this month's issue.

2021 Northeast Fisheries Outlook

Written by John Sackton, Seafood.com News

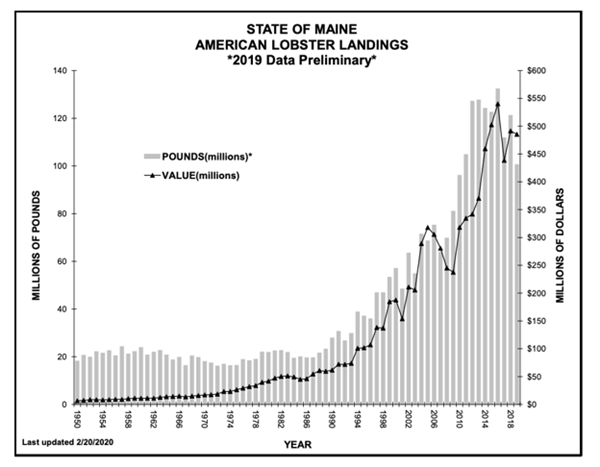

New England is home to the most valuable fishery in the United States, primarily due to lobster and scallops. Lobster landings were worth $684.3 million in 2018. Approximately 90% are landed in Maine, with 7 or 8% landed in Massachusetts.

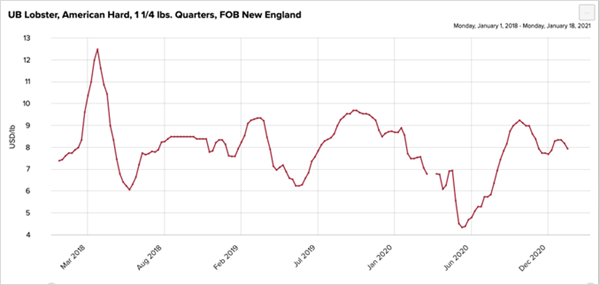

Figure 1. Hard Shell 1 ¼ lb Lobster Wholesale Price, FOB Boston 2018-2020

Source: Urner Barry

From May through the first half of August, wholesale lobster prices fell up to 46% below the 5-year average. Prices recovered in the second half of 2020 due to lower than expected landings and higher than expected demand. This outcome was not foreseen last spring, when many lobster fishermen contemplated parking their boats due to fear of market prices not covering their costs.

Landings in Maine have been trending downward over the past few years. Although data for 2020 is not yet available, most observers in the industry think landings will be significantly below 100 million pounds for the first time in nine years.

Figure 2. Maine Historical Lobster Landings 1950-2019

Source: Maine Department of Marine Resources

The silver lining of the pandemic for the New England industry, and for seafood producers across the country, has been the increase in seafood consumption, even accounting for losses in restaurant sales.

According to recent figures from the National Fisheries Institute’s Global Seafood Marketing Conference, in 2019, seafood sales were split 50/50 between retail and foodservice or restaurants. This has been true for decades.

In 2020, for frozen seafood, the foodservice share fell to 36%, while the retail share grew to 64%. In dollar terms, retail grew 37% while foodservice declined 24%. The result was a net gain in overall sales across the entire seafood category of around 8%.

One of retail seafood’s biggest winners was lobster, where retail sales soared 87% based on Nielsen IRI data. This dramatic shift in demand explains why lobster prices recovered to more normal levels in the second half of 2020.

But the industry faces monumental environmental challenges.

The lobster fishery has been strongly impacted by global warming. Oceanographic features mean the Gulf of Maine has been warming faster than practically any other ocean area on earth. The lobster population has been moving north, as they seek colder waters. The nine years of over 100 million-pound landings in Maine came about as more lobsters moved into areas open to fishing. Meanwhile, landings along the southern coast of New England and in Long Island Sound have declined.

There is no guarantee that lobsters will stop moving. Maine could experience a decline in landings as a greater portion of lobsters migrates to Canadian waters in the coming years. The recent declines may be a harbinger of this, but it is too soon for firm conclusions.

The lobster industry in Maine also faces another problem due to climate change: increased interactions with the critically endangered North Atlantic right whale.

There are only about 400 remaining North Atlantic right whales. Since 2017, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) estimates about 40 have died. While climate change may be the species greatest threat, the most visible causes of mortality are ship strikes and fishing gear entanglement. The added weight of lines and traps weakens the whale and, in some cases, leads to starvation. Aerial surveillance shows approximately 25% of the population gets entanglement scars each year.

In an attempt to reduce these entanglements, Maine fishermen have adopted weaker breakaway lines, and recently began using a marking system to identify any gear from Maine seen in an entanglement. But the large scale of the Maine lobster fishery requires that it be part of the primary solution for protecting right whales.

More regulation may be coming: A lawsuit brought by environmental groups in the spring of 2020 successfully argued that NOAA, the federal agency that regulates fishing, has failed to sufficiently protect the whales. NOAA regulations require fisheries not to cause additional mortality to endangered species.

The lobster industry may not have many choices in responding to this crisis. The Marine Stewardship Council (MSC), a nonprofit which certifies seafood as sustainable, suspended its certification for Maine lobster after the lawsuit, but not for Canadian lobster. Many retailers require their suppliers to either be MSC certified, or to have some equivalent protection plan in place. Without an acceptable way forward, the Maine industry may be at a disadvantage in the retail marketplace, especially as Canadian suppliers could continue to meet demand.

Maine fishermen argue that they are not the primary cause of the right whale problem yet are being asked to bear the greatest costs for mitigation.

Other New England fisheries experienced much the same roller coaster as the lobster fishery this past year.

Scallopers, whose products are also highly dependent on foodservice, initially saw lower prices which have since recovered. Scallops are the fourth most valuable fishery in the U.S. and have made New Bedford, Massachusetts consistently the highest value port in the nation.

Fresh seafood also had distribution hiccups. However, the overall increase in demand for seafood was a rising tide that has helped most of the industry.

The one sector substantially left behind has been shellfish aquaculture. In Massachusetts, which harvests around 50 million farmed oysters per year, the State’s Division of Marine Fisheries says that between May and October, sales were down 43%. Many unharvested oysters have grown too large for their normal markets, further losing value, and acting as a drag on farmers ability to restock next year.

Oysters have not been able to make the jump to retail seafood because shucking an oyster is simply not a skill that many Americans can master. The industry boomed on a surge in oyster bars, as young people embraced oysters more than most other seafood. But this all took place in the social context of bars and restaurants and did not transfer to home consumption. The pandemic will undoubtedly drive a significant number of small oyster farms out of business, which is likely to be a longer-term consequence for the New England aquaculture industry.

Editor: Chris Laughton

Contributors: Christopher Wolf, John Sackton and Chris Laughton

View previous editions of the KEP

Farm Credit East Disclaimer: The information provided in this communication/newsletter is not intended to be investment, tax, or legal advice and should not be relied upon by recipients for such purposes. Farm Credit East does not make any representation or warranty regarding the content, and disclaims any responsibility for the information, materials, third-party opinions, and data included in this report. In no event will Farm Credit East be liable for any decision made or actions taken by any person or persons relying on the information contained in this report.

Tags: aquatic, commercial fishing