September 2, 2020

International Trade Update

Contents

Volume 14, Issue 9

September 2020

Click here for a PDF version of this month's issue.

International Trade Update

International trade has been a major issue affecting U.S. agriculture in recent years. The U.S. has had contentious relationships with several major trading partners around the world resulting in a roller coaster of news and developments around global trade, which has been further complicated in recent months by the COVID-19 pandemic. Agriculture, as one of the U.S.’s most significant export industries, has often been significantly affected by these developments.

Perhaps the most rocky international relationship the U.S. currently has is with China. Relations between the world’s two largest economies and major trading partners have deteriorated with issues of contention, including the COVID-19 pandemic, the fate of Hong Kong, sanctions against Xinjiang over alleged human rights abuses, and technology issues, such as proposed U.S. bans on the apps TikTok and WeChat.

Beijing’s commerce ministry announced on August 20 that the two sides would talk “in coming days,” after President Trump postponed further discussions on the Phase One trade deal because he was unhappy with China’s handling of the coronavirus. China appears to hold hope that the upcoming trade talks, agreed upon when the Phase One deal was signed in January, will prevent the further collapse of bilateral relations between the two nations as U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer continues to engage with his Chinese counterparts.

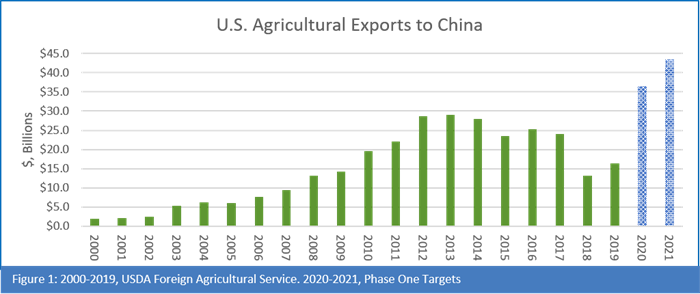

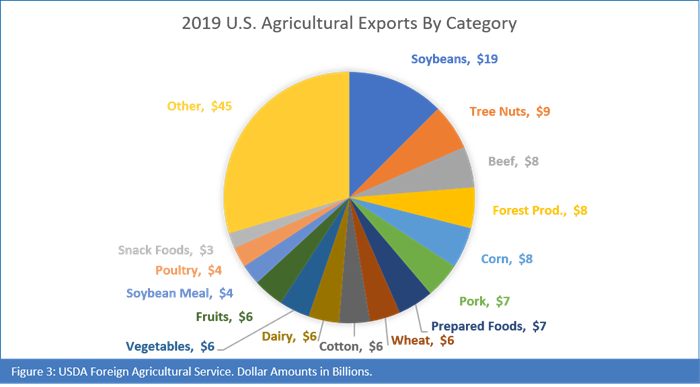

At stake in this back-and-forth are billions of dollars in trade. In 2018, the U.S. imported $539 billion worth of goods from China, and exported $120 billion, including $13 billion worth of agricultural and related products.1 In 2019, while trade of goods between the two nations declined overall to $452 billion in imports and $106 billion in exports, U.S. agricultural exports increased to $16 billion. The Phase One trade deal promised an additional $200 billion in Chinese purchases of U.S. goods and services over the next two years. Included in the $200 billion, were an additional $32 billion in agricultural goods over the 2017 baseline of $24 billion, for a total of $36.5 billion in 2020 and $43.5 billion in 2021, an extremely ambitious goal, which many analysts were skeptical of from the start.

China has indeed increased its purchases of U.S. products, particularly for manufactured goods, but as of June, it was only on pace to meet 47% of its targeted purchases and only 24% of its agricultural commitments. In other words, China has purchased only about $8.7 billion worth of agricultural goods in the first half of 2020 and would need to import nearly $28 billion worth of ag products between now and December 31 to meet the target, a prospect that seems increasingly unlikely.2

China is not the only source of trade concerns for U.S. agriculture. The U.S. and the European Union (EU) have a long-simmering trade dispute over subsidies to aerospace manufacturers Airbus and Boeing. While the origin of the dispute may be narrow, the fallout has been felt across a range of industries. The U.S. has imposed tariffs on approximately $7.5 billion of European imports while the EU retaliated in a similar fashion.

In addition to tariffs on aircraft, the U.S. has imposed tariffs ranging from 15-25% on European dairy products, fruits, seafood, pork, olives, spirits, clothing and some manufactured goods. The EU has responded similarly, targeting many agricultural products.

Another trade issue the U.S. has long complained about is Europe’s attempt to prohibit the use of “geographical indicators” by non-European products around the world. These include the use of names for a variety of wines, spirits and foodstuffs linked to a specific region, such as requiring the term Bourdeaux be applied only to wine produced in the Bourdeaux region of France, or that Parmigiano cheese must come from the Parma region of Italy.

Finally, the U.S. has taken issue with a number of non-tariff barriers to trade with Europe, such as limitations on the import of genetically modified agricultural products.

Recently, however, a sign of a potential thaw in relations has emerged as the European Commission agreed to end tariffs on U.S. lobster,3 a welcome development for an industry hit hard by trade disputes and the pandemic. In return, the U.S. will reduce its tariffs on a number of European goods. Both sides hope that this agreement will open the door to further normalization of trade relations.

Finally, there is trade between the U.S., Canada and Mexico. Many businesses reliant on North American trade breathed a sigh of relief when the USMCA was ratified earlier this year. While the changes in the USMCA were fairly modest compared to its predecessor, NAFTA, the potential lapse of an agreement was cause for concern. When NAFTA took effect in 1992, trade between the U.S., Canada and Mexico was approximately $300 million annually. Today, it exceeds $1 trillion as supply chains have become increasingly integrated between the three nations. Thus, the implementation of the USMCA was more about avoiding disruption in trade than increasing it.

Still, the agreement promises new export opportunities for some U.S. industries, including the dairy sector. When the agreement was signed, the International Trade Commission projected that U.S. dairy exports could increase by more than $314 million per year. Much of this was based on increased access to the protected Canadian dairy market, a provision in the agreement that was controversial in that nation. Now that the USMCA has been implemented, some in the U.S. Congress are arguing that Canada is not fully complying with the agreement, by continuing to favor domestic producers and processors over those from the U.S.

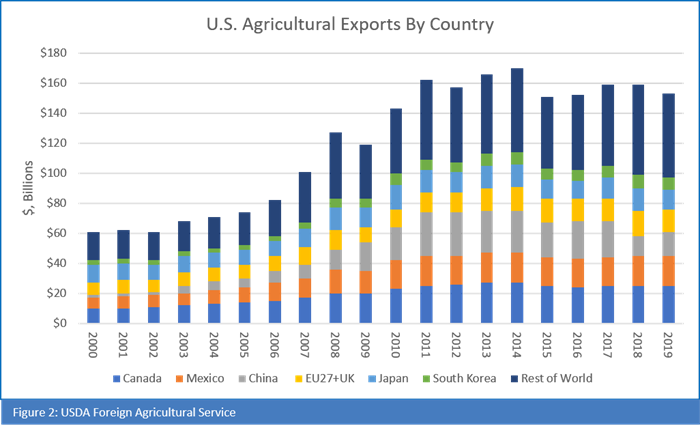

In summary, international market access is essential for U.S. agriculture, and has become significantly more important since 2000. American farmers are among the most productive and efficient in the world and, increasingly, are producing far more than our domestic population consumes. Thus, access to the 96% of the world’s population that lives outside our borders is critical. Even for producers whose products are not directly exported, domestic supply and demand, and market prices are significantly influenced by export markets.

There are certainly a number of legitimate issues for U.S. trade negotiators to raise with our partners around the globe. Addressing these issues, including tariffs and non-tariff barriers, protection of intellectual property, trademark enforcement and more, with as minimal fallout as possible makes the job of U.S. trade negotiators difficult, but essential, for U.S. agriculture.

1 Includes agricultural goods, as well as ethanol, biodiesel, forest products, and fishery products.

2 Peterson Institute for International Economics, US-China Phase One Tracker.

3 BBC News, “US Wins End of EU Lobster Tariffs in Mini Trade Deal,” August 21, 2020.

Editor: Chris Laughton

Contributors: Deanna Pellegrino, Tom Cosgrove and Chris Laughton

View previous editions of the KEP

Farm Credit East Disclaimer: The information provided in this communication/newsletter is not intended to be investment, tax, or legal advice and should not be relied upon by recipients for such purposes. Farm Credit East does not make any representation or warranty regarding the content, and disclaims any responsibility for the information, materials, third-party opinions, and data included in this report. In no event will Farm Credit East be liable for any decision made or actions taken by any person or persons relying on the information contained in this report.